When we respect our environment, we respect ourselves (Gyalwang Drukpa)

Before telling you about the influence that global warming has on glaciers and the climate of Khumbu, I would like to highlight the high degree of awareness that people of these valleys have about the impact their way of of life, the increase of construction during the last 60 years and the tourist activities, have on the Khumbu’s environment. If we add to this the effects of global warming on the temperature and level of precipitation (water and snow) throughout this area, we have an explosive cocktail producing a very important changes in the surface of forests, glaciers and glacial lakes.

During my trips through the glaciers of the Khumbu high areas I could ascertain everything I had read in several disclosure and research papers on the impact of global warming on the glaciers of the Himalayas and especially in the Khumbu area .

In this area there is a large concentration of glaciers that are in a strong regression. Of the four most important I could visit three: the Ngozumpa, the Khumbu and the Nangpa. My unexpected departure from Nepal due to the Covid-19 left me half a day away from stepping on the last one I had yet to see, the Imja and its glacial lake the Imja Tso.

The Ngozumpa Glacier

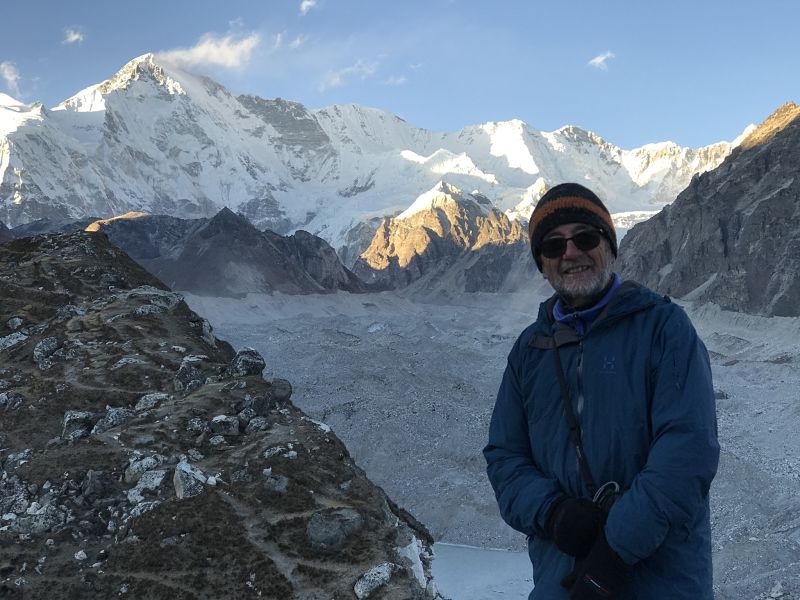

It is the longest glacier of the four. In August 2019, with my friend Pasang, I tried to get it but the bad weather and a little snowfall when we were in Gokyo prevented us from doing so. We went back in late November, when the fall season was over, and on the afternoon of the 26th, once settled in the Namaste Lodge in Gokyo, we climbed to the ridge of the lateral moraine of the glacier and… what a awesome and thrilling views! In front of us it was an ice river 32 km long, which comes down from Cho Oyu (8,188 m), on the Tibet border, to a below Gokyo. The immensity of the glacier and the sunset’s light made it unique.

Sunset at the Ngozumpa glacier

The Ngozumpa glacier and the Cho Oyu in the backgroung

Lateral moraine of Ngozumpa glacier

The next morning, at dawn, from the top of the Gokyo Ri (5,360 m), we were able to enjoy unforgettable views of the glacier and the glacial lake of Gokyo, with a backdrop of 5 peaks over 8,000 m, Everest included.

Dawn in Gokyo

Gokyo Ri (5,360 m)

View from the Gokyo Ri top

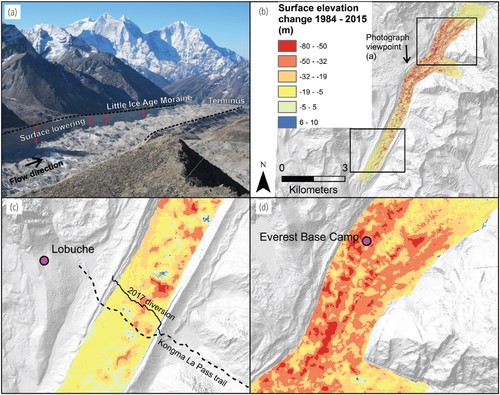

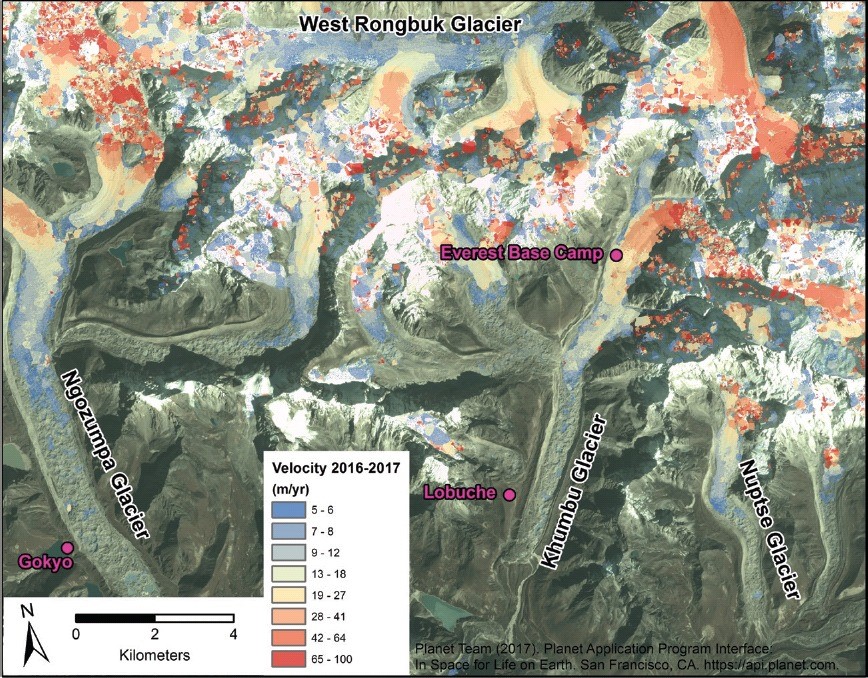

As you can see in the photos, glaciers are largely covered by debris that give it the appearance of dirty ice just sprinkled by small green or grey lakes. The loss of ice mass is evident in the photos where the height of the side moraines of the glaciers can be seen.

The Khumbu Glacier

It is the second longest in the area and the highest in the world. It extends from below Everest to a little further down of Lobuche (4,900 m).

Southern view

Lateral moraine view

Northern general view

In early September 2019, we trekked along the villages between Namche and Gorak Shep, the last inhabited place before Everest Base Camp (EBC). The monsoon was still very active but luckily the weather opened a small window that allowed us to see the glacier all the way from Lobuche to the EBC, as well as all the peaks that surround it: the pyramid of Pumori ( 7,165 m), the ridge and summit of the Nuptse (7,864 m), the Lhotse (8,516 m) and Everest (8,848 m)

This glacier is currently only 10 km long and is shortening about 30 m. every year. In the EBC area, the glacier moves down 70 m / year while in the lower part it moves only at 10 m / year. Another fact that helps us to understand the rate of melting of this glacier is that EBC is currently more than 50 meters lower than when Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary summited the Everest for the first time, in 1953.

View from the trail to Gorak Shep

Ice formations

Everest Base Camp

The glacier in the EBC area with the ice fall in the background on the right

The Nangpa Glacier

This was the first area I visited after arriving in Namche. We followed the valley that goes up to Thame and from there we followed the valley that climbs to the Nangpa La pass. This trail, which follows the course of the Bhote Koshi River from Thame to the north, is the route used by caravans of merchants and yaks to travel between Khumbu and Tibet through the Nangpa La at 5,716 m., to that China completely closed this pass.

Frontal moraine of the Chhule glacier

Frontal moraine of the Nangpa glacier

We followed it to Chhule (4,600 m), the last settlement in the valley, currently uninhabited, where several glaciers converge, the most important of which is the Nangpa. From here, the trail to Tibet continued over this glacier to the top of the Nangpa La pass. It is also the trail used by the first Sherpas to reach the Khumbu just over 500 years ago.

From above the place of Chhule we could see the glaciers coming down the valleys and the footprint they have left for centuries, now more visible with the retreat of the ice due to global warming. At this point, the front moraines of several glaciers converge, forming a chaotic and spooky landscape. Despite being the third longest in this area, the place where it is located is the most open of the four glaciers and is of impressive grandeur.

The Imja Glacier and the case of the rapid growth of Lake Imja Tso

This glacier is the smallest of the four glaciers referenced in this post and is located at the foot of the Imja Tse (Island Peak, 6,189 m).

The interest of this glacier is not so much because of its characteristics but because it is the origin of the glacial lake Imja Tso, located at 5,000 m., at the end of the glacier. It was formed in the 1950s with the beginning of the melting of this glacier, which moves back about 75 m each year while the lake grows about 2.5 Ha yearly. As this posed a high danger of the lake bursting and causing severe flooding throughout the Solukhumbu district, in 2016 a drain had to be built to drain it.

Confluence of Imja Glacier and Imja Tso Glacial Lake, 2011 – Photo: Daniel Alton Byers

Lake Imja Tso once drained in 2016 – Photo Sanjeep Phuyal – Kathmandu Post

As the mass of water grows, the influence of its temperature increases the rate of melting of the glacier. This phenomenon observed in the Imja Tso suggests that in a few years a glacial lake will also form at the end of the Khumbu Glacier.

Conclusion

According to a study published in 2009 by Dr. Lhakpa Norbu Sherpa and sponsored by ICIMOD (International Center for Integrated Mountain Development), between 1992 and 2006 Khumbu glaciers decreased by 9 Ha. and the area covered by snow was reduced by 11,344 Ha. This phenomenon caused the simultaneous increase in the surface of glacial lakes (most are less than 50 years old) and the appearance of many new lakes, which increased by 236 Ha. This gives us an idea of the magnitude of the change that is taking place.

Because glaciers help regulate the climate and keep temperatures lower, as glaciers disappear a loop is created that raises temperatures at an exponential rate.

In the short term, as glacial melting increases, no water supply problems are expected, but in the long term, as glaciers run out, the region may face a water shortage crisis of difficult solution. This is just one example of the myriad effects that climate change could have here and is also happening on a global scale. Because the long walks through those valleys left me a lot of time to think and meditate about everything I tell you in this post, this anonymous phrase comes to my mind: “We are not what we do or what we think, we are only the footprint we leave ”.