Most people who have gone to Nepal have come back home with a few strips of those five-coloured flags, perhaps best known as prayer flags, which we then put in a place we think that they look nice or maybe they remain in a drawer. But have we ever wondered about their origin and meaning? I must admit, no.

A few days ago, during a blessing ceremony and the subsequent placement of these flags on a ridge, I had the opportunity to discover the origin and meaning of such symbolic elements. I must admit, it was one of the most interesting experiences I have had so far, in this project. That is why I want to share it with everyone who follows my blog.

These flags, called lungpar in the Sherpa language, are made up of a series of small square or rectangular flags, joined by a string or thread, with printed prayers or mantras, and with the simple idea that wind and water will be charged to widespread them to all beings in the universe, and not, as is often mistakenly believed, to bring them to the gods.

Flags with prayers and mantras

Flags on top of a ridge

They place them mainly on ridges, cliffs or mountain passes, but also on the roofs of houses. The flags, blue, white, red, green and yellow, are placed in this order, either from top to bottom or from left to right. These colours mean the sky, clouds, stone, water and earth, or the five elements: air, water, fire, earth and space.

Sherpas believe that once these banners are blessed by a lama and placed in one of the mentioned places, they will bring luck, happiness, health and longevity to their families. That is why, to coincide with the beginning of the Tibetan year, they bless the flags and place them, on the days marked as auspicious within the first 20 days of the first month of the year. The number of flags in the set hanging by each family must be greater than the sum of the ages of the people who make it up.

Long strips of flags

Prayers and mantras that takes the wind

They are usually renewed once a year. The placement must be done without touching the existing ones and the remains of the old ones cannot be thrown away. They must be burned or left in one of the many sacred caves near the monasteries.

Last Sunday, March the 1st, which was the 7th day of the first month of the year 2147 in the Tibetan calendar, with my friend Pasang we had gone to the village of Thame and he wanted to take the opportunity to go to the Buddhist monastery above the village to bless the flags he brought from his home in Namche.

Thame monastery

Thame monastery seen from above

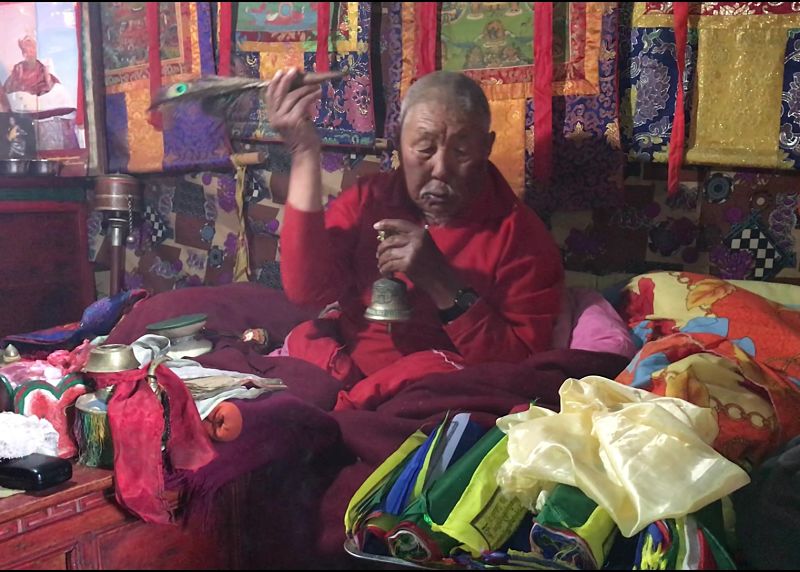

Early in the morning we went up to the monastery to go to the house of one of the lamas living there. An 88-year-old man who has lived in this monastery all his life, received us with great kindness. There, in the small room where he lives, we put the four rolls of flags on a tray and he started reciting mantras in Tibetan for a good while. While chanting these mantras and burning incense, he would play small instruments and scatter large rice grains over the flags and across the room. The ritual, and the atmosphere of the small room where it took place, had a captivating effect on me, despite not fully understanding the meaning.

Incense for blessing

The Lama blessing the flags

After the blessing ceremony, we headed up the hill above the monastery, to the place my friend had chosen to hang the flags. Then he, with great care, lit a small bonfire with juniper twigs and for a few moments passed the flags over the juniper smoke. He then climbed further up and spliced and extended them out until they had formed a large and colourful arch with the flags flying, then he tied them carefully so that they did not touch the ones already in the same place.

Choosing the place to hang the flags

Small juniper bonfire

When it was done, he returned to the bonfire to pray and throw a handful of rice mixed with cereal seeds, which the lama had prepared during the blessing ceremony.

Extending flags

Final prayer

Once all this was done, and after having covered with some stones what was left of the little bonfire just to avoid the bonfire remains spread with the wind, we only had to undo the way down to the monastery. We made it light and silent. A silence, that of my friend, which I still interpreted as spiritual gathering, lasted until we arrived again at the monastery.

Once there, we set off on our way home to Namche, very happy. He for having fulfilled a ritual in which he believes, and I for having learned what these flags mean by the Sherpas. And the truth is that I couldn’t find a more sublime way to symbolise the desires of luck, happiness, health and long life for all of us.