Description of the region

The Sherpas came to these valleys just over 500 years ago from eastern Tibet, in several migratory waves between the 16th and 18th centuries, and settled in what is now known as the Solukhumbu district, formed, from north to south, by the areas of Khumbu, Pharak and Shorong (Solu in Nepali).

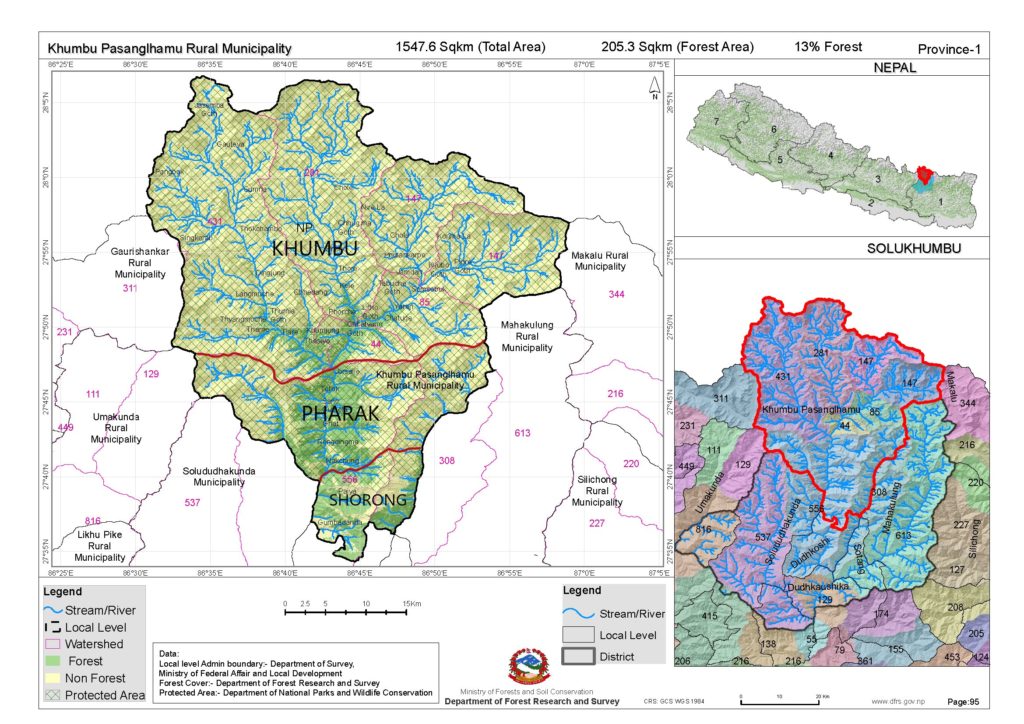

The last Constitution of Nepal approved in 2015 established a new administrative organization with provinces, districts and municipalities. As a result, the Khumbu Pasang Lhamu Rural Municipality (KPLRM) was created, comprising the Khumbu, Pharak and northern Shorong areas, from the village of Kharikhola to below Lukla. This territory is where I develop my project.

The name of this municipality honors Pasang Lhamu Sherpa, the first Sherpa and Nepalese woman to climb the Everest. It was April 22, 1993, and as she descended, she and her husband died when they were just on the southern summit of the Everest due to bad weather that suddenly got worse.

The evolution of the Sherpa population

According to the American anthropologist Sherry Ortner, the first Sherpas arrived to Khumbu in 1533 and twenty years later, in 1553, they extended to the Shorong area further south and at a lower altitude than Khumbu. They lived in complete independence and peace for almost two centuries until in 1717 they were subjugated by a Hindu dynasty and in 1772 by the Gorkha kingdom, to which they had to begin paying taxes. Apart from this issue, no less important of course, they continued to enjoy a high level of autonomy as no one approached such remote and hard-to-reach areas.

This was the case until the 1960s when, due to political tensions between the two neighboring states, China and India, the Nepalese government began to open government offices and to establish police and army detachments there. This, and the declaration of a national park in 1976 initially managed by non-Sherpas officials, meant the loss of the ability to manage their own interests.

Despite the few data available, it is known that in the Khumbu area alone, in 1836, there were 169 households and in 1957 there were already 596. Already with data from modern censuses, we know that in 1991 households were they had increased to 830 and according to the last available census (2011) 1,031 were counted.

According to the latest census in all three areas of the KPLRM, in 2011 there were a total of 2,433 households, which indicates that almost half of the households in this territory were located in the Khumbu area. , that is, in Namche and the villages above.

Khunde in 2019

Thame in 2019

In terms of population, in the KPLRM as a whole, 8,243 people lived there in 2001 and in 2011, 8,969, of which only 5,212 (58%) were of the Sherpa ethnic group. These figures show the change in the composition of society in this territory, which in just over 60 years has gone from being 100% Sherpa to 58% on average. If we look at it by areas, we see that the proportion of Sherpa population increases from south to north and with the height of the areas, 40% in the Shorong (Solu) area, 52% in Pharak and the highest in the Khumbu, 74%.

This is due to two factors. One is the arrival of people of other ethnicities, some destined for the area by the country’s government (officials, police and army) and most attracted by the job opportunities offered by tourism.

The other factor is the emigration of Sherpas to Kathmandu or abroad which, in just 10 years (2001-2011), has reduced the Sherpa population by 500 people (10%). This trend is on the rise for two reasons. The first is that as the economic level of families improves, they decide to settle in Kathmandu or abroad, or send their children to study there from an early age. The second cause is that the increase in the number of schools and students and the conviction of parents that the education of their children is the best guarantee that they can have a better life than their own. It makes that every time there is more girls and boys studying in Kathmandu. In both cases there is a complete lack of return to the place of origin. This fact may seem a contradiction, or perhaps it is, since the increase and improvement of education in these valleys, undoubtedly a positive fact, at the same time causes the better prepared youth settle outside the territory that saw them to born.