The last post of the Sherpa Life project

The worst of a farewell isn’t not to have to leave up everything you’ve known but realizing everything you haven’t come to know

One of the first things I learned when I arrived at Khumbu was that that ubiquitous, almost magical word, Namaste, which everyone uses in Nepal to greet each other, is not a Sherpa word but Nepali. Its use is so widespread that when Sherpas address a foreigner, they never use their equivalent Sherpa: Tashi Delek (or Trashi Dele). They were these words that opened more doors for me and gave me more smiles when I visited Sherpa people during my stay in those valleys. This and two other expressions, khole phep (goodbye) and thuuche thuuche (thank you) is all my baggage for social relationships, in the Sherpa language, that I took home. Many will think, limited, right? Well yes but learning Sherpa language was not part of my goals when I prepared the Sherpa Life Project.

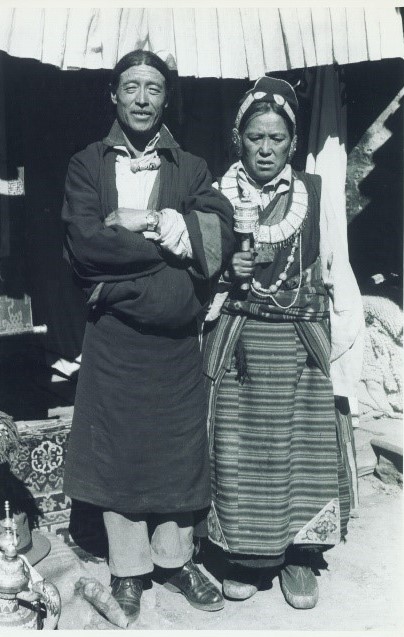

With the Tenzing’s brother and sister in law

Dawa Sherpa chopping grass for cattl

This introduction helps me to start this post, which is a brief reflection to answer the questions that many friends, including the subscribers and followers of my blog, have asked me over the past year: it has been worth the sorry? What is your assessment of your experience?

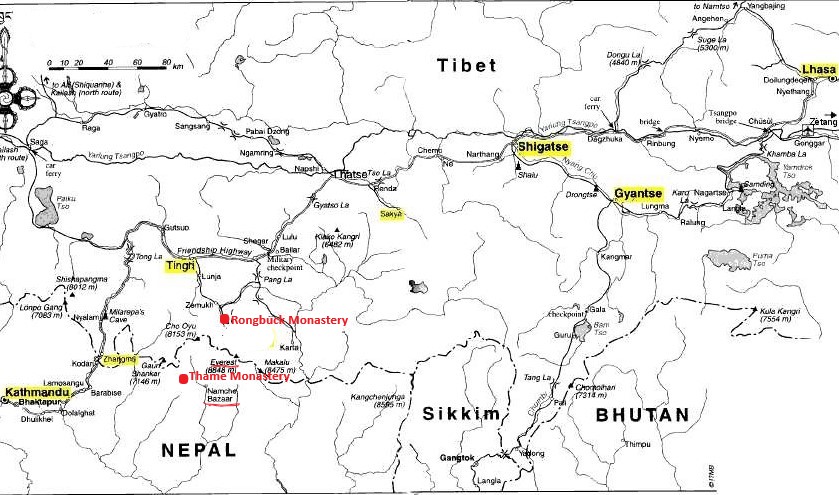

To put it in context I want to remember what the three objectives of the project were:

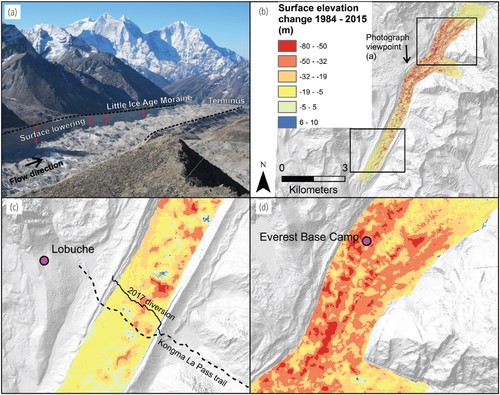

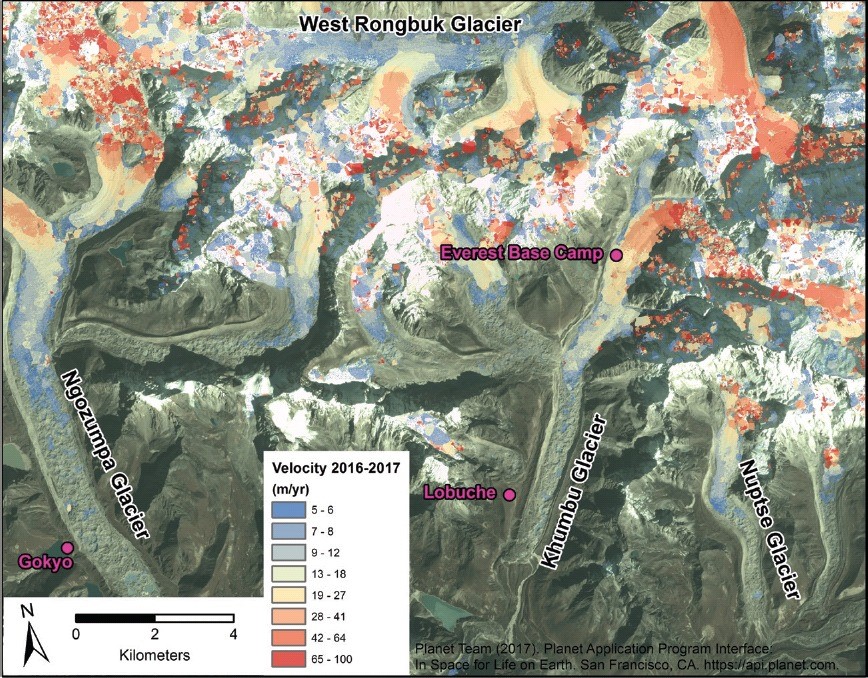

- To observe, know, understand and disseminate the life of the Sherpa inhabitants of the Khumbu valleys in Nepal, in the 21st century

- To analyze the economic, social and cultural impact of trekkings, expeditions and tourist activities on the inhabitants of these valleys, in the last 75 years

- To analyze the impact that the arrival of information and communication technologies has had on the life of Khumbu people

A POSITIVE BALANCE

To achieve these goals, I planned to spend a whole year in the Khumbu, to live with the Sherpas of those valleys, beyond the tourist seasons. It seemed to me a practical, perhaps unscientific (or not at all) approach to the reality that I guessed was very interesting, though unknown to me. That entire year became, even before it started, two 5-month periods due to the limitation of visa periods by the Nepalese government. And finally, as you know, they have only been 7 months because of this virus that surrounds us and has changed our lives.

Dining room of my hotel, in August

The same dining room in October

To the question of whether it was worth it, I must tell you that the answer is: very, very much! I have to admit that when I left home, despite being very motivated and convinced of what I was going to do, I also had my worries about how I would adapt to a way of life so different from ours. Both for the physical challenge (health, diet, high altitude, always walking, age) and emotional (far away from home, family and friends; will I get bored? will it take me too long?). So, I am very pleased with how I overcame these two challenges.

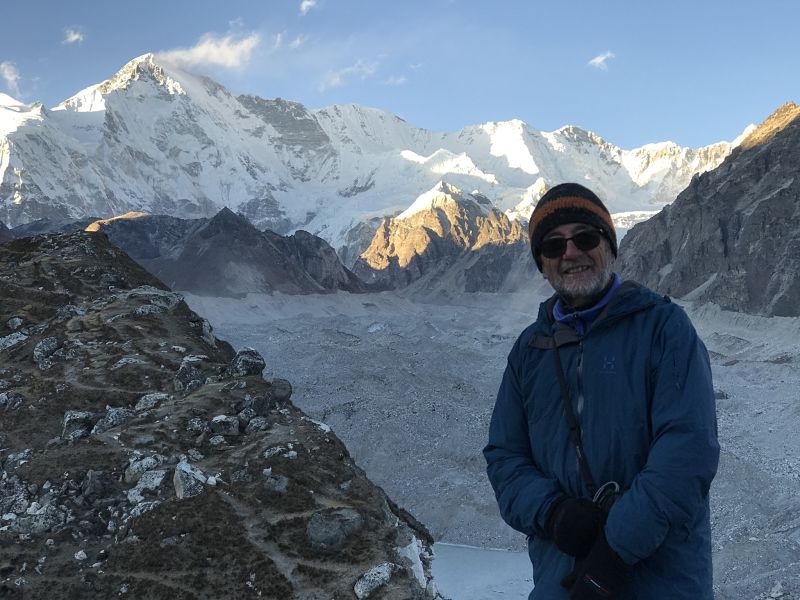

With Pasang in the Everest Base Camp

With my friend Pasang in the Gokyo Ri top

Health was the biggest concern I had and luckily it respected me a lot. In this I was very reassured by the research project that Dr. Carme Comellas, from the CIMETIR of Clínica Sant Josep (Althaia) in Manresa (Spain) (https://www.clinicasantjosep.cat/serveis-medics/unitats-especialitzades/cimetir ), decided to carry on about the impact that a long stay in very high altitude (between 3,500 and 5,500 m) could have in the health of a person over 70 years. This forced me to do daily check-ups of various health parameters, which I periodically sent to Dr. Comellas and of which she returned with her comments to me. This follow-up gave me a peace of mind that for myself I probably would not have had.

The enthusiasm to develop the project, the good acceptance and the support from local people (especially my friend Pasang and his whole family) made the emotional challenge easier for me. The technology available in most of Khumbu areas, allowed me to feel closer to home. And the family visit in mid-October was like a reset for me (and for them, too, I’m sure).

MY FAMILY VISIT

At Tengboche Monastery

Pasang’s family farewell

Ready to leave Namche

It has been such an intense life experience that at no point did I feel bored or lose my enthusiasm. In fact, there was so much to discover and learn, so many people to meet, so much to tell, that the days passed quickly and plenty of findings and emotions.

As for the 3 goals I set for myself, I consider them well achieved. The 27 posts I posted and the pictures on the web (www.sherpalifeproject.com ) and Instagram (#sherpalifeproject) I think are the most tangible example of the result. I’m just as proud of what I’ve been able to do and, above all, of have been able to share it with so many people.

THE PROJECT IN FIGURES

In this post it seemed me interesting (or at least curious) to add a few figures on the development of the project. Here they are:

Project duration: 6 and a half months

Days spent at the Khumbu: 177

Walking distance: 1,215 Km

Walking time: 435 hours

Maximum height: 5,643 m (top of Kala Patthar)

Cumulative elevation gain: 56,023 m

Cumulative elevation loss: 60,904 m

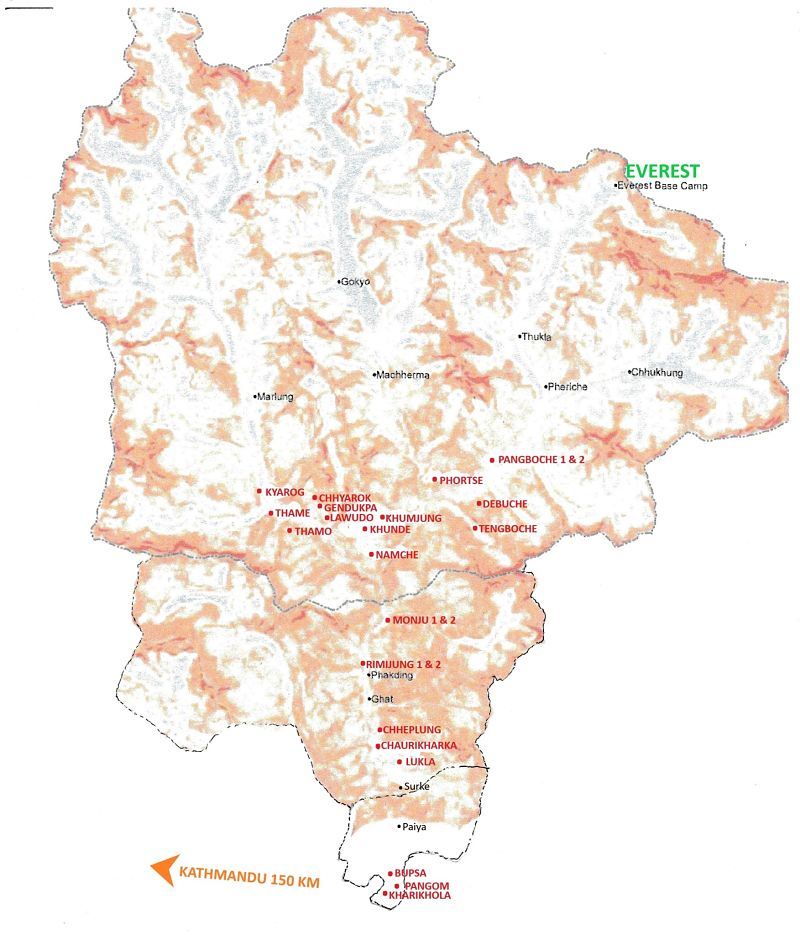

Villages or hamlets visited: 50

Schools visited: 13

Monasteries visited: 23

Hospitals visited. 2

Health posts visited: 11

Ama Dablam from Khunde, in winter

Thamserkhu form “my house” window

KHOLE PHEP (GOODBYE)

It’s been 12 months since that first post I titled Preparing the Road from Catalonia to Namche and what was once a project is now a reality. What was the anxiety of starting the adventure now is the satisfaction of everything I’ve learned, all the people I’ve met, all the places I’ve visited and all the support I’ve had.

It’s time to open a parenthesis between what I’ve done so far and what I’d like to do from now on. Some exhibitions, audio-visual material, outreach talks and maybe a book. If you count among those friends who have insisted to me to write a book, I will try. I’ve a lot of material and I’m very excited. We will see what comes of it.

So, as a Catalan folk song says, it’s not a goodbye forever, it’s just a goodbye for a moment. An instant that will be a bit long but in the end I hope to meet you again to continue sharing. Thuuche thuuche (thanks) for being there and see you soon!