The context

After visiting all the schools from Lukla upwards, I find it interesting to write a post about education in Khumbu valleys.

Only 58 years ago the first modern school was created in this area. Until then, monasteries were the only educational institutions where students who wanted to become monks were educated, and so most lay people were left without any formal training.

In 1960 there was a first attempt to establish schools in Namche and Chaurikharka, when the Nepalese government sent a few teachers there, but it turned out that there weren’t buildings to teach!

The establishment of schools with suitable classrooms and qualified teachers began in 1961 when Edmund Hillary built the Khumjung School. Soon other neighbouring villages asked for help to have their own school. This is how the schools of Thame (1963), Pangboche (1964) and Phortse (1968) were created in the upper part of the Khumbu.

Sir Edmund Hillary monument, Khumjung school

The oldest clasrroms (1961) in Khumjung School

Since there were no literate people in Nepali and English here, Edmund Hillary had to look for qualified teachers in the Sherpa communities of Darjeeling, India.

From Lukla onwards, there are now eleven primary schools and two upper secondary schools that house more than 1,500 students.

One fact that caught my attention is that in all the schools I have visited, every morning, before the classwork starts, students gather in the playground, form by levels and they do some gymnastics exercises, some schools at the pace of drums and others following the rhythm of a song sung by older students. They also say a prayer and sing the Nepali national anthem.

Singing the Nepali anthem, on the Student’s Day

Ready for gymnastics, Khumjung School

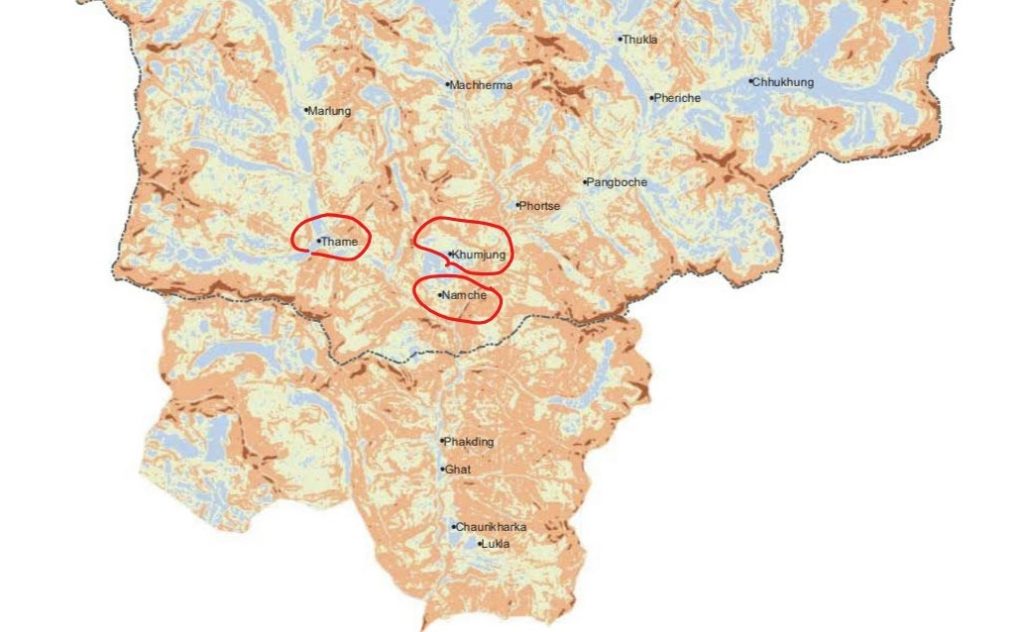

To complement this introduction, I think it is appropriate to talk about three schools located in three villages in the upper part of Khumbu: Khumjung (3,790 m), Thame (3,750 m) and Namche (3,450 m).

Khumjung Secondary School (Hillary School)

Created by Edmund Hillary in 1961, started with two classrooms and was the first school in all of Khumbu.

It currently consists of 17 buildings, with two levels of kindergarten (3 to 5 years) and 10 levels of primary and secondary with 21 teachers and a total of 314 students (half girls and half boys). Classes are held in English, Nepali and Sherpa are also taught. For the learning of Sherpa they have only one teacher, who is a lama.

Playground and classrooms in Khumjung School

Computer classroom

At the same school there is a small residence for non-Khumjung teachers. For students who are far away, there are two buildings (hostels) in the same school, where they live throughout the course. They only go home during long vacation periods. In the village there are two private hostels more.

Himalaya Primary School in Namche

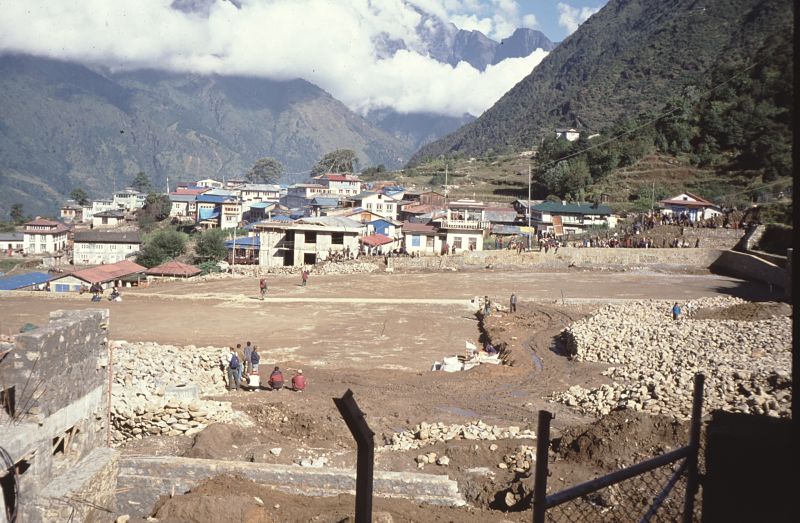

Namche’s first school was created in the 1960s and the current one, which consists of 3 buildings, was built between 2014 and 2015. It opened on May 24, 2015, a day before the strong earthquake that shook Nepal. The school was virtually unharmed and after a few minor repairs it was put into operation a month later.

Teaching in Nmache School

Going into classrooms, Namche School

The school has 13 classrooms and accommodates 220 students who can study there until level 8 and then continue to level 10 at Khumjung school. There are 12 teachers, of whom the government only pays 2 and the other are paid by the parents with a monthly fee of 1,000 rupees (about 8 €) per students well as donations from private sponsors. As in Khumjung, the teaching is in English but Nepali, and more recently Sherpa, are also taught.

The school has its own hostel where about 25 boys and girls live throughout the school year. In the village there is also another private hostel where about sixty boys and girls live.

Thame Basic School

This is a small school, established in 1963, just 2 years after Khumjung. It is now completely new as the 2015 earthquake completely devastated it. There are only 24 boys and girls from 5 to 13 years old. They are 6 teachers and have 7 levels. They must mix girls and boys of different levels in the same classroom. They teach in the Sherpa and Nepali languages.

Their main concern is the small number of students they have. That’s why they have created a kindergarten for children from two and a half years old, to guide them to school.

Classroom in THame School

New buildings of Thame School

One of the factors influencing the small number of students is that they cannot stay to live in the village because there is no hostel and due to this families from places far from Thame prefer to send them to Khumjung or Namche and thus avoid that they have to make long walks to and from school. For the next school year, this will no longer be a problem as a hostel is being built at the same school. This is expected to double the number of students in 3 or 4 years.

A family’s conviction that their child can study

To end this post, I want to tell you about the effort and conviction of a family I met, and especially of the mother, to take the child to school. It’s an example that impressed me.

This is a family living in the village of Thamo, an hour’s walk from Namche. They have a 5-year-old boy and they decided to take him to Namche school, but their financial situation does not allow them to face the annual expense of about $ 1,000, so that he cann’t stay in the school hostel.

Convinced of the importance of education for her son, every day the mother accompanies her son, on foot, to the school in Namche (10 in the morning), and back to Thamo. There are days when she takes advantage of the trip to carry some load and thus earn some rupees. In the afternoon again to Namche to pick up her son (4pm) and to Thamo back home. This every day of the school year. 4 hours walks the mother and 2 the child!

An example of a family that has clear in mind the value of education for their child’s future. The day I met them they were halfway back home. The mother was tired but smiling as we were talking and the child eager to go from here to there as if it was a game. Like in those documentaries of the “Way to School”, but live. Simply exemplary and awesome!