“I was lucky today, I woke up and am alive, I have this precious life and I will not waste it” (Buddhist philosophical thought)

All these months I have been living in the Khumbu have allowed me, among many other things, to discover Buddhist monasteries from a very different perspective than when I visited them during a trekking. I also understood that Buddhism, more than a religion in the sense the Christian world gives to religion, is a philosophy and a way of life for the Sherpa people.

I have found that monasteries (gompa or gonde in Sherpa language), together with schools, hospitals and health posts, are one of the three basic infrastructures of today’s Sherpa society. From the Westerners point of view, it may seem strange to consider monasteries at the same level as the other two infrastructures, but the fact is that, in the 21st Century, this is the case and I would venture to say that it is the same throughout Nepal.

Thame monastery

Tengboche monastery

Until 60 years ago, the absence of schools and health facilities, made monasteries the centre of Sherpa life. Lamas were almost the only literate people, and they had a huge influence on the entire population. In addition to religious activity, they established lay rules in villages and established some of religious festivals and celebrations also with a very important social role because, with the lack of the current communication systems, they were the only occasions that locals in the valleys could meet family and friends. That is why all celebrations last for several days.

BUILDING MONASTERIES

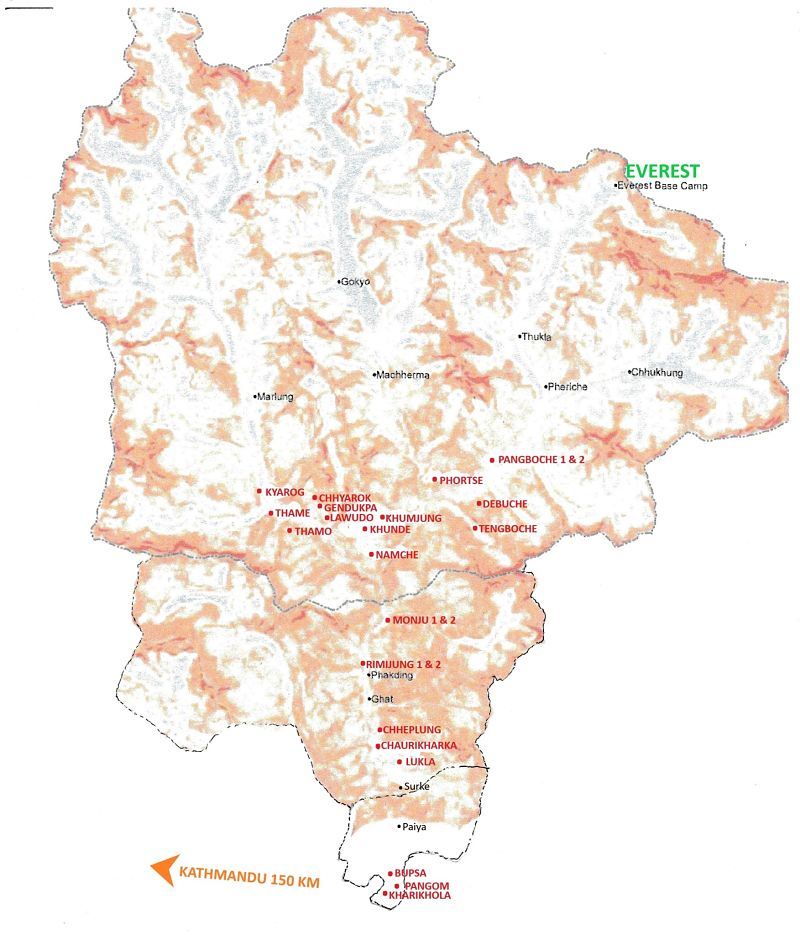

In the area where I developed my project, that is, from Kharikhola to the upper valleys that reach the bottom of the mountains, there are 24 monasteries, of which I have visited 22. The oldest were built under the initiative of the religious leaders of those times. The first three were founded between 1667 and 1672 by three Lama brothers who were part of the third generation of Sherpas established in the Khumbu: Sangwa Dorje built Pangboche, Ralpa Dorje Thame and Khenpa Dorje Rimijung.

Map with monasteries in red

Chaurikharka monastery inside

Later on, monasteries were built thanks to economic contributions and the work of Sherpas of each place. Over the past 50 years some new ones have been built, such as the anis (Buddhist nuns) monastery of Thamo in 2002, the one of Kharikhola in 2008 or the Tekhongma of Rimijung in 2019, with significant economic contributions from foreigner people and institutions, which also funded the reconstruction of many monasteries damaged by the two earthquakes of 2015. Maintenance is mainly funded by the contributions from each monastery community.

Private monastery in Monju

Rebuilding the Nandoling monastery

Although most monasteries belong to the Buddhist community, some are private as they were built and maintained by a family and are part of the family property. One of the surprising things I discovered during this period is that anyone can build a Buddhist monastery and it doesn’t require any permit.

THE LAMAS LIFE

For 300 years lamas used to be married and the management of the monasteries passed from one generation to the next, following the family lineage. It was not until the second half of the 20th century that some monasteries began to evolve into celibate monasteries. Even today, in most monasteries coexist married and unmarried lamas.

A common occurrence in all monasteries is the ups and downs in the number of lamas living and their activity in them, which mark the splendour and decline times. Another aspect to note is the dramatic decline in new lamas over the last twenty years, mainly as a result of widespread family planning in the country, which has reduced the number of children in families. Because the tradition was that the third boy became a lama, and now most families have only two children, there are few new lamas. One of the consequences is that in most monasteries there is only one lama for maintenance purposes, or nobody lives there.

The ani living alone in the Chhyarok monastery

Novices of Thame monastery

Of the 22 monasteries I have visited, only four have a permanent community of lamas (Lukla, Rimijung, Tengboche and Thame) and two have a community of anis (Debuche and Thamo). The life of the lamas in the monasteries is essentially studying, praying and meditating; organizing community celebrations and festivals; and conducting private ceremonies (weddings, funerals, and other family ceremonies).

Lamas performing a ritual in Thame

Lamas performing a dance of the Mani Rimdu in Tengboche

In places where there are no lamas or they are not enough, are the lamas of the nearest monasteries, who cope with these duties. The lack of lamas is also balanced by the village lamas, who are people who, without being lamas, are properly trained in conducting private ceremonies.

TULKU, THE REINCARNATED LAMAS

One aspect that has caught my attention from day one, and is difficult for me to understand, is the existence of reincarnated lamas in various monasteries and the procedure by which they are recognized.

The reincarnated lamas, called Tulku in Tibetan, come from the successive reincarnations of the 25 major disciples of Guru Rinpoche who was an 8th century Buddhist master, also known as the Second Buddha. Tradition has it that when a reincarnated lama is about to die, his disciples ask him to reincarnate, and he decides whether to do so or not. If he decides that, then, once he dies his disciples wait for signals from a boy born in the area after his death. It can take time, usually years, until a boy is identified as a possible reincarnate. After a series of tests done according to very strict protocols, ends up being recognized as a reincarnated lama. He is then transferred to his predecessor’s monastery and begins a period of training that lasts for many years and includes university education, often in foreign countries.

Meeting with Tengboche’s Abbot

Guru Rinpoche image

During my visits to the monasteries I had the opportunity to meet two tulku. One is the abbot of Tengboche Monastery, Ngawang Tenzin Zangbu, aged 85, with whom I had the opportunity to talk about my project and his vision for the Sherpas future. He is a man with a great influence in the area, not only religious but also political. The other was a 9-year-old boy, at Thame Monastery, who was reincarnated as the former tulku of the monastery and is now in the beginning of his education process. A boy apparently like anyone else who, during a monastery ceremony I attended, was sitting at a prominent place higher than all the other lamas, sometimes reading the sacred books, and sometimes looking at the ceiling and looking bored. As any other child would had done.

THE BUDDHIST RELIGIOUS BOOKS

There were no books in the Buddha’s time, and it was not until 4 centuries later that his disciples wrote down his teachings in various books in the Sanskrit and Pali languages and later were translated into Tibetan. The two most important collections are the Ka-gyur and the Ten-gyur. The Ka-gyur (108 volumes) records the Buddha’s teachings and words as recorded by his disciples. Ka means Buddha’s word and gyur means translated.

Ka-gyur of Namche monastery

Ka-gyur of Chaurikharka monastery

The Ten-gyur (226 volumes) is a set of commentaries on the Ka-gyur written by Buddha’s followers. It is believed that there are about 8 Ten-gyur in the Solukhumbu.

All the monasteries have a collection of these religious books who keep on the shelves in the main hall where the ceremonies take place.

In addition to these collections in monasteries, there are also other collections of books for home use. They are the Boom and the Domang.

The Boom books in a private house in Khumjung

Prayer instruments

Boom are 16 books with 100,000 verses that are like a diary of Buddha’s thoughts. Many families have the Boom and call lamas 3 or 4 times a year to read them.

The Domang is a single book with an extract from the most important parts of the Ka-gyur, which most families have, and they read at least it once a month.

THE ROUTE OF THE MONASTERIES (link)

There are three aspects of the monasteries that make them interesting to visit: their colourful architecture and decoration, their history and the places where they are located. That is why I thought it might be useful to open a new section of the web that is like a small guide, with a map and a list of all the monasteries in the area, with the basic data of each one.