“Do not take refuge in the past, do not dream on the future, concentrate your mind on the present” (Buddha thought that, in my opinion, nowadays we may apply to the times we are living)

Sherpa’s religious and cultural rituals remain almost unchanged for the most important passages of life: birth, marriage, and death. The Sherpas “inner culture”, which drives the important passages of life, remains relatively unchanged despite the obvious changes in many aspects of the “outer culture” such as housing, clothing or educational and economic opportunities.

Despite the months I have been living in this area, I haven’t had a chance to attend any of the three passages of life, except a brief observation of a funeral prayer, but I’ve been able to talk with people about it. This and some research on anthropological studies and other publications, allows me to tell you how Sherpas live the three main steps of life.

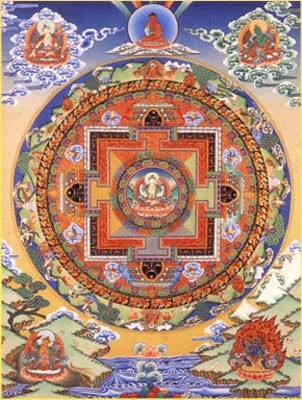

The Wheel of life is a mandala, a complex picture representing the Buddhist view of the universe. The Wheel is divided into five or six realms, or states, into which a soul can be reborn.

THE BIRTH

Tradition says that children should born once the three stages of the marriage have been completed, but the most common is that children are born before the Demchang (last stage of the marriage process). This way is considered a bit “polluted” among Sherpas, but they solve it with the offering of holy water by the father’s family to the mother’s family as a gesture of purification. Easy and practical!

Families attach great importance to having at least one boy to ensure the continuity of the clan, which in Sherpa society follows the lineage of the father. However, the birth of a girl is equally welcome because in their society women are considered, at least in theory, just like men. Then, in practical terms and from a westerner eyes, this is no longer the case in many respects.

The child’s naming is the most important ceremony of the beginning of life, apart from the birth itself. The identity of the Sherpas consists of three names. The first name of Sherpa child, girl or boy, generally comes from the day of the birth. This fact has an effect of uncertainty because when you have to meet someone whose name you only know, until you meet him or her or see a picture, you don’t know if you’ll meet a woman or a man. Other names are also given after a lama consultation.

The second name is chosen by the family by drawing lots from a wide range of names that distinguish between women and men. They are names with meanings such as fortunate one or long life, for boys or healthy and joyful or wise one, for girls.

The third name is the same for everyone: Sherpa. It is the sign of belonging to the Sherpa ethnic group.

THE LONG WAY OF MARRIAGE

Sherpa wedding traditions are still followed very strictly in Khumbu and with slightly changes among the Sherpas living in Kathmandu or even abroad. Currently, the celebration of the last wedding celebration of Sherpas living in Khumbu, usually takes place in Kathmandu during winter season, as it is a time when there is no work in Khumbu and many families spend the winter in Kathmandu.

Until a few years ago, marriages were arranged between families but today this has changed, and most are love marriages. According to Buddhist ideas, to marry a girl who is unwilling or to arrange a marriage by the parents, is a sin (digba).

Marriage is a long process that involves three stages and can last up to three years or more. The process begins with the Trichang which is the marriage proposal that the boy’s family makes to the girl’s family, it is the ritual of engagement. After a while, the second stage arrives, the Longchang, which is the confirmation ceremony by the bride and groom and the families, of which everything goes ahead. Before the third stage there is a small but important step in deciding the exact year and date of the final wedding ceremony.

Finally, on the agreed day, the Demchang begins, which is the ceremony consisting of a great celebration, which can last for days, during which the exchange of rings takes place. Since there is no tradition of dowry in the Sherpa culture, the bride receives the part of the family inheritance that belongs to her at the time of the wedding and is when she formally goes to live with her husband. There is no tradition of honeymoon. They themselves say, half-jokingly, half seriously, which is because after the big celebration they have no strength or money left for the honeymoon.

As a result of the length of the whole process and the high cost of the wedding ceremony, it is increasingly common for the bride and groom to live together and have children from the second stage onward, and many couples no longer celebrate the Demchang.

In terms of divorce, it is quite common among Sherpas and is estimated to happen in 30% of marriages.

THE STEP TOWARDS THE NEXT LIFE

The funeral rituals of the Sherpas are strictly followed by both those living in Khumbu and Kathmandu. When a person dies, one or more lamas are immediately called to perform the rituals to generate good positive energy for the deceased.

Because the heat of the body may leave through the soles of the feet, hands, eyes, nose, ears, mouth, or the top of the head, the spirit of the dead person is considered to follow the same direction as the heat. If the spirit of the dead leaves from elsewhere it is considered that the next life will be bad. If it comes out through the nose or eyes it will be able to re-incarnate in an animal or person. If it comes out from the head it may go to their heaven, called Dewachen.

Although there are different customs, the body is usually kept at home for three days during which the lamas and the family perform rituals to help and guide the soul in the transition to the afterlife. After these days, the body of the deceased is taken to the place of cremation, accompanied by a procession with lamas, religious music, flags, umbrellas, banners and incense.

Cremation ceremony

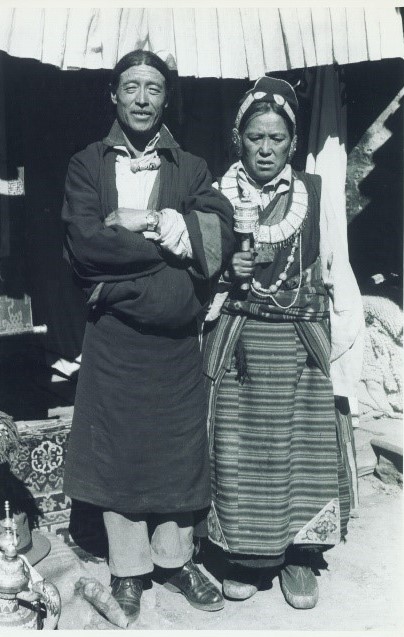

Sherpa funerary ritual

After cremation, once a week for seven weeks, a lama performs a ritual (Dun-tsig) at the deceased’s home. Within three or four weeks after the death, the family also makes offerings called Sheto which is the ceremony that the family can perform for the welbeing of the soul of the deceased. These offerings can last between three and fifteen days, depending on the financial situation of the family. Every evening, the family puts a tsampa offering on the embers of the fire for the spirit of the deceased and offers food and drink to family and friends who accompany them.

Cremation place, in Pangboche

Funerary memorials (Chulung), in Pangboche

The remains of the cremation are mixed with clay and turned into Buddha figurines or medallions called tsawar that are stored in a memorial cairn (chulung) or in a cave under a large rock. This happens after 49 days of death, which is the space of time that they consider to be between two lives. At the end of this period, the person’s next life is determined and may be reborn.

And from this point the wheel of life of Sherpas restarts, which Tengboche Rinpoche, the re-incarnate lama and abbot of Tengboche Monastery summarises it thus: “When you die, what do you take with you? Your money, your house, even your wife and family do not go with through”